4 Things to Keep in Mind While Benchmarking Data Engines

Yevhenii Niestierov

4 Things to Keep in Mind While Benchmarking Data Engines

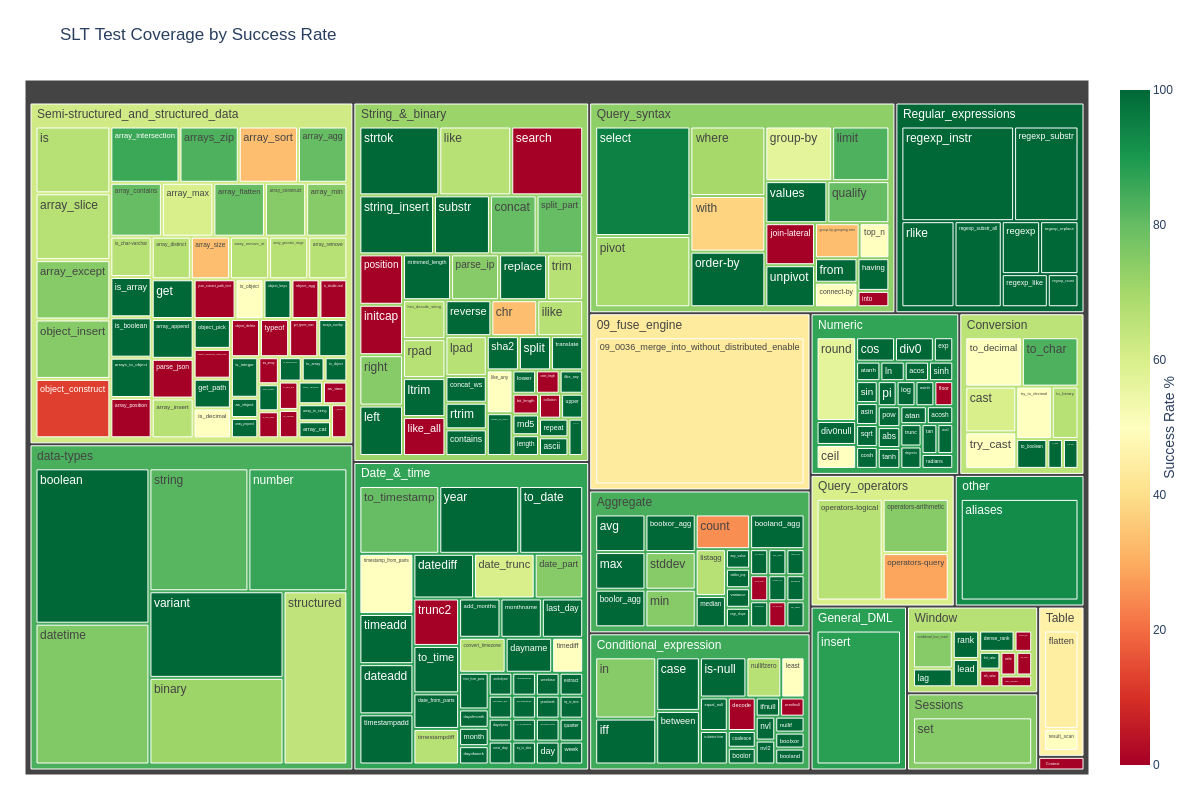

I set out to run what I thought would be a straightforward SF 1000 TPC-H benchmark. Instead, it turned into a multi-day investigation chasing elusive performance anomalies. Was it challenging? Yes. Should you have to go through the same ordeal? Absolutely not.

The Setup

My goal was to benchmark data engines against a 1TB TPC-H dataset. I was testing their performance across two storage scenarios.

- Instance: r6gd.metal EC2 node (64 vCPUs, 512 GiB RAM) on Ubuntu 24.04. The ‘d’ means it comes with local NVMe storage, which was perfect for my “Local Parquet” test.

- Dataset: TPC-H Scale Factor 1000 (~1TB), generated via tpchgen-cli.

- The Scenarios:

- — Local Parquet: Data on the local NVMe drive.

- — Parquet-S3: Data in an S3 bucket.

My investigation led to 4 key findings that can impact any benchmark.

Finding #1: The “Local” Disk Isn’t Ready “Locally”

This was my first major roadblock. I chose an r6gd.metal instance because the ‘d’ means it has fast, local NVMe “Instance Store” drives. I assumed I could just cd / and start my tests.

I was wrong.

By default, an EC2 instance boots from its EBS (Elastic Block Store) volume, which is a network-attached drive. The super-fast NVMe drives are just sitting there, invisible to the file system-unformatted, unmounted, and waiting as raw devices (like /dev/nvme1n1, /dev/nvme2n1, etc.).

Before I could even run my first test, I had to write a setup script to:

- 1. Automatically detect all available NVMe instance store disks.

- 2. Join them into a high-performance RAID 0 array (using mdadm) for maximum throughput.

- 3. Format the new RAID device (I used XFS).

- 4. Mount it to a folder I could actually use (/mnt/local-ssd).

- 5. Update /etc/fstab so this mount would survive reboots.

You can find it in the Embucket benchmark repository.

The Takeaway: Your “local” test is running on a slow network disk (EBS) unless you explicitly script the setup of your fast NVMe drives.

Finding #2: My “Cold” Run Was Secretly “Hot” (The OS Cache Trap)

This was the core mystery. My “cold” runs (Iteration 1) for the generated dataset were chaotic.

— Sometimes Iteration 1 took 10.49s.

— My “hot” runs (Iterations 2 & 3) took ~10s.

How could my “cold” run be just as fast as my “hot” runs? The md5sum proved the parquet files were identical.

The culprit was the OS Page Cache, and the tpchgen-cli script was the one setting the trap. When I ran free -m to check my system memory, I found the evidence:

Before tpchgen-cli:

| total | used | free | shared | buff/cache | available | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mem: | 514740 | 4395 | 513344 | 2 | 189 | 510344 |

buff/cache was empty (189 MB).

After tpchgen-cli:

| total | used | free | shared | buff/cache | available | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mem: | 514740 | 5463 | 162892 | 2 | 350119 | 509276 |

buff/cache exploded to 350 GB. The very act of generating the 1TB dataset (writing it to disk) caused Linux to cache the entire thing in system RAM.

This meant the 10.49s runs were “fake cold” runs. I was actually reading from the OS RAM cache.

The Takeaway: Never trust a “cold” run immediately after generating data. You must manually clear the OS Page Cache before every single cold benchmark to get a true disk-read measurement.

# This became a mandatory step before every test

sudo sync && echo 3 | sudo tee /proc/sys/vm/drop_cachesFinding #3: A 3x Performance Gap from Data Layout (1 File vs. 20 Files)

Once I started correctly clearing the OS cache (Pitfall #2), my results finally stabilized. The new, “true cold” time for my tpchgen-cli dataset (let’s call it Dataset B) was ~17.3 seconds for Q1.

But while investigating the cache issue, I tested another dataset (Dataset A) to check my hypotheses. This one was also TPC-H SF1000, but I had created it using DuckDB’s internal TPC-H generator and its export database command, like this:

# This command created Dataset A

duckdb -c "CALL dbgen(sf=1000); export database 'tpch_data' (format parquet);"This command is convenient, but it has a crucial side effect: it creates one giant, monolithic parquet file for each table (e.g., lineitem.parquet).

In contrast, Dataset B (tpchgen-cli —parts 20) created 20 smaller, separate parquet files.

When I ran the same “true cold” test (with a cleared cache) on both, the results were not even close:

- Dataset A (DuckDB export) Q1 Cold: ~50.2 seconds

- Dataset B (tpchgen-cli) Q1 Cold: ~17.3 seconds

This was a 3x performance gap from a cold disk read, just by changing the file layout. I wasn’t just testing TPC-H; I was benchmarking “monolithic file” vs. “partitioned files” without realizing it.

DuckDB is a parallel engine. When it saw 20 files, it spun up 20+ threads and read them all simultaneously, maxing out my NVMe RAID. When it saw one giant file, it created an I/O bottleneck, and performance was 3x worse.

The Takeaway: How your parquet files are physically structured is a critical performance lever. A parallel engine needs parallel-friendly data. The method you use to export your files (e.g., a default export database command creating one file vs. a tool that partitions into many) can be the single biggest factor in your benchmark.

Finding #4: Believing a Local NVMe RAID is Always Faster than S3

My next assumption was simple: local is fast, network is slow. My high-performance, multi-disk NVMe RAID 0 array - which I had just painfully configured - would obviously destroy S3 in any I/O test.

I was wrong again.

I ran a heavy, I/O-intensive query (TPC-H Q5, a 6-table join) that needed to scan and join lineitem, customer, supplier, orders, nation, and region.

| Scenario | overall_time |

|---|---|

| 📁 Local Parquet (RAID 0) | 41.9 sec |

| ☁️ S3 Parquet | 24.9 sec |

That’s not a typo. S3 was 1.68x faster than my local, high-performance RAID 0 array.

How is this possible? The answer lies in the type of I/O.

My RAID 0 array was configured for maximum sequential throughput (perfect for reading one giant file from start to finish).

But DuckDB’s query plan was the exact opposite. It spawned 60+ parallel threads, all trying to read different chunks from different giant tables (lineitem, customer, supplier) at the same time.

This pattern is a massively parallel, random-ish I/O workload.

- - This workload choked my local RAID array. It created massive I/O contention. The profiler proved it: the CPU was starved, waiting for the disk (effective parallelism was only ~49x).

- - S3, on the other hand, is a distributed object store built for this exact scenario. It happily served all 60+ parallel HTTP GET requests without breaking a sweat. The CPU was well-fed (effective parallelism ~60x) and the query finished almost twice as fast.

To make things even weirder, a different query (a simple, CPU-bound aggregation, TPC-H Q1) showed the opposite result, where Local (17.1s) crushed S3 (45.4s). In that case, the local disk could keep up, and the “CPU tax” of S3’s SSL/TLS overhead on 60+ threads became the bottleneck.

The Takeaway: Don’t assume “local” means “fast.” For highly parallel query engines, the aggregate throughput of a distributed system like S3 can easily beat a local RAID array, especially on complex, multi-table join workloads. Your bottleneck isn’t just “disk vs. network”; it’s sequential vs. parallel I/O.

Conclusion

If there’s one conclusion to take away from this multi-day debugging story, it’s this: benchmarking is a minefield of false assumptions.

What surprised me most is how easy it is to draw the wrong conclusions from the “obvious.” Each finding started with a confident assumption - that local disks are ready to go, that a freshly written dataset is cold, that file count doesn’t matter, and that local storage must always beat S3.

None of these turned out true.

Benchmarking forces you to unlearn these shortcuts. Every layer - hardware, OS, storage, and data layout - has its own traps. The real skill isn’t just in running the benchmarks, but in catching the invisible variables that distort them.